Overcoming

Challenges

to Operating

Reactors

By J. Scott Peterson, Nuclear Energy

Institute.

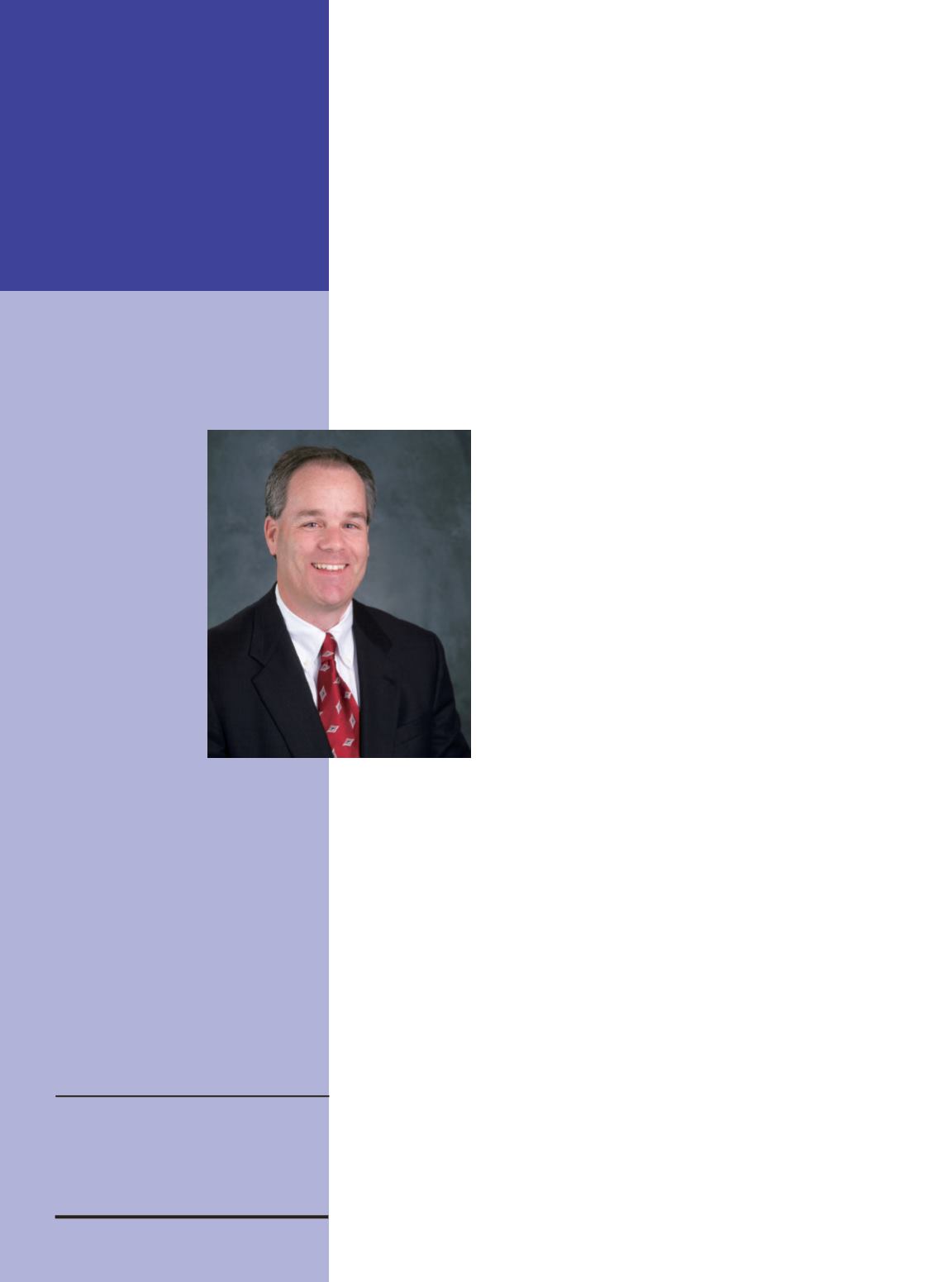

J. Scott Peterson

Mr. Peterson directs the Nuclear Energy

Institute’s communications activities,

including media relations, coalition

management, advertising, editorial and

creative services,

public opinion

research and industry

communications.

At NEI, Mr. Peterson

also has served as

senior director for

communications.

He has led major

branding programs to

promote the benefits

of nuclear energy.

Mr. Peterson also

has directed public

affairs programs that

support enactment of

federal legislation,

including the Energy Policy Act of

2005 and congressional approval of the

nation’s nuclear fuel repository site,

and recognition of nuclear energy in

international climate change policy.

Mr. Peterson received a bachelor’s

degree in journalism from the University

of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Additionally, he has completed the

Reactor Technology Program for Utility

Executives at the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology.

An interview by Newal Agnihotri,

Editor of Nuclear Plant Journal, at

the American Nuclear Society Utility

Working Conference in Amelia Island,

Florida on August 13, 2014.

1. How can we alleviate the merchant

plant situation to turn that challenge into

an opportunity?

That will be challenging, but it’s

possible given time and changes in some

of the market rules on a state or regional

level. Looking at the factors that are

in play in these markets, every state is

different, and there are different dynamics

in each of the Regional Transformation

Organizations (RTOs).

Different states have varied pressures,

in part because they have different rules

and different renewable mandates. About

half of the states have renewable mandates

of up to 30 percent of that state’s electricity

generation.

In addition, there are pressures from

low-priced natural gas. The more gas we

bring out of the ground,

the more pressure that

puts on utilities with

reactors in competitive

markets. The only

real chokepoint for

natural gas is the

delivery system. For

example, in January

2014, with the polar

vortex, we saw some

of the disruptions

in the gas supply

that can happen for

electricity generation.

When you had the

coldest temperatures

in January, natural gas

that normally goes to electricity production

got diverted for home heating and other

uses. So, while you have firm delivery

of natural gas for electric generation on

a normal day, when you hit the extremes,

particularly in winter, you’re going to have

chokepoints when you can’t get the gas you

need, so you have to switch to oil at those

power plants that can make that switch.

In the PJM market in Mid-Atlantic states,

they came very, very close to the point

where they were going to have blackouts.

And In South Carolina, they actually took

customers offline for a number of hours

because most heat down there is electric

heat. And so, when you had record

temperatures through the Tennessee Valley

and into the Carolinas and you had coal

plants and gas plants that were coming

offline because of the cold temperatures,

they simply couldn’t meet the electricity

demand that they had because of the frigid

temperatures.

We’ve learned from the polar vortex

experience that our reserve margins in

many regions are really, really low when

you have extreme weather. In the next

10 years, most of the reserve margins

in almost all markets will be below the

minimum requirements, unless you start

adding generation to the grid.

So, you have the pressures of low-

priced natural gas, mandates for renewable

electricity, plus the production tax

incentives for wind and solar that may

allow them to come in under the market

price and then use that production tax

credit to lift up their profitability. They’re

undercutting the market, in some cases

at very large volumes. In some markets,

reactors face the triple threat of renewables,

low-priced natural gas and low-priced coal.

And that’s simply too many economic

pressures even for a very efficient, well-

operating plant to take in an open market.

That was the situation with Dominion’s

Kewaunee nuclear energy facility and the

company simply had no choice but to shut

down. If you could move that plant to a

number of other states, it would still be

operating today.

Once you shut down a nuclear plant,

you don’t bring it back. And in the case

of Kewaunee, this is an interesting case

study. Wisconsin is now looking for 700

megawatts, which is almost the exact rating

of Kewaunee, to bring on to the system in

two or three years because now they have a

deficiency of power generation. So, we’re

making shortsighted decisions based on

short-term price signals and now those

organizations that run the markets are

starting to look at how they price some of

the attributes of nuclear energy differently

because they aren’t yet recognized or are

priced too low.

One example of that is capacity

auctions in the regional markets. There are

two prices established in those markets-- a

capacity price that companies get simply

to have the power plant there and available

to produce electricity when needed and an

energy price for the output. The capacity

prices typically have been very low and

are set by natural gas plants. What PJM is

doing now, and we expect some movement

on this in September 2014, is looking at

energy capacity prices differently, to say:

okay, what’s really going to be available

when we need it in the most extreme

periods. So, they’re taking the lessons

learned from the polar vortex and applying

them to their markets to ensure that

28

NuclearPlantJournal.com Nuclear Plant Journal, September-October 2014