Maintaining

Public Trust

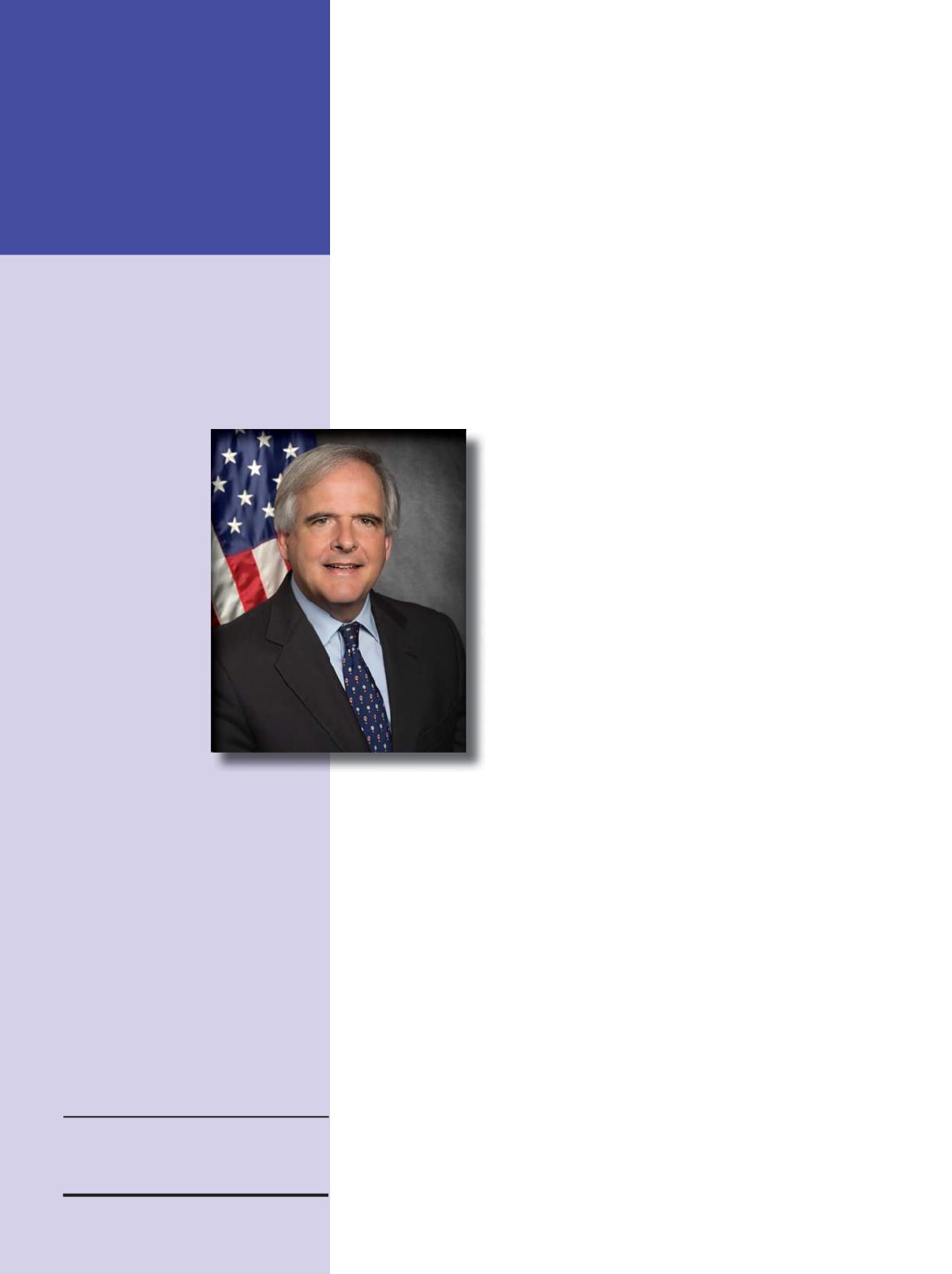

By Stephen G. Burns, U.S. Nuclear

Regulatory Commission.

Stephen G. Burns

The Honorable Stephen G. Burns was

sworn in as a Commissioner of the U.S.

Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC)

Nov. 5, 2014, to a term ending June 30,

2019. President Obama designated Mr.

Burns as Chairman of the NRC effective

Jan. 1, 2015.

Mr. Burns has a

distinguished career

as an attorney both

within the NRC

and internationally.

Before returning

to the NRC, he

was the Head of

Legal Affairs of the

Nuclear Energy

Agency (NEA) of

the Organisation

for Economic

Co-operation

and Development

in Paris. In that

position, which

he held since April 2012, Mr. Burns

provided legal advice and support to

NEA management, carried out the legal

education and publications program

of the NEA, and provided advice and

secretariat services to the Nuclear

Law Committee and to the Contracting

Parties to the Paris Convention on Third

Party Liability in the Field of Nuclear

Energy.

Mr. Burns received a bachelor’s degree,

magna cum laude, in 1975 from Colgate

University in Hamilton, New York. He

received his law degree with honors

in 1978 from the George Washington

University in Washington, D.C.

Excerpt of remarks of NRC Chairman

Stephen G. Burns at the 2016 Regulatory

Information Conference on March 8,

2016.

Today, of course, we have a

consolidated headquarters complex, 100

operating reactors with a sharp decline in

anticipated new ones, and, well we know

the path forward for high level waste

disposal is still muddled.

Yet safety and security remain our

fundamental regulatory objectives. We

are still bound by the language of the

Atomic Energy Act, with a focus on “ad-

equate protection” and “reasonable assur-

ance,” broad terms in a statute purpose-

fully left free of prescriptive language by

the Congress.

Or as the U.S. Court of Appeals for

the DC Circuit said in Siegel v AEC in

1968, somewhat paraphrased – The

Atomic Energy Act sets out a regulatory

scheme under which

broad responsibility

is given to the

a d m i n i s t e r i n g

agency as to how

it shall achieve the

statutory objectives.

In other words,

the

NRC

has,

over the decades,

wrestled with how

much is too much

regulation and what

regulation is deemed

necessary to be “safe

enough.” The bottom

line is always how

much risk are we

willing to take?

How much risk is acceptable? It must be

acknowledged that the NRC does NOT

regulate to no risk – to zero risk. Not in

1978 and not now.

“Adequate protection” is a difficult

phrase to explain to lay audiences when

adequate in the usual vernacular signifies

just OK. For us, of course, it means the

Commission must consistently and over

time use its broad discretion to impose

requirements it believes meets this

mandate. We can be neither too lax nor

too strict. And we must not conduct our

decision making in a vacuum. We must

consider real life and actual operating

experience, and we must weigh public

and stakeholder input to guard against

making decisions in isolation.

This balancing act is the essence of

what I call the regulatory craft.

Part of the regulatorycraft, I believe, is

listening to the opinions of those outside of

the NRC. While the NRC is independent,

that does not mean we are isolated. It’s

important the NRC communicate with

and engage in meaningful dialogue with

the industry, the Congress, the states,

local governments, non-governmental

organizations, international entities and

the public. You know – like what we’re

doing today at the RIC!

We can be independent while still

listening and considering the opinions of

others.

In a speech I gave last year, I talked a

bit about my regulatory philosophy.

I am registered as an Independent –

not a Democrat or a Republican. Along

those lines, I believe I am independent

in my thinking and philosophy. I don’t

adhere to a rigid ideology that compels

a certain outcome each time, though I

believe I’m predictable in my approach of

evaluating each matter on a case-by-case

basis and applying rules deliberately and

consistently across the board.

I am also independent in that I’m

open to new ideas and solutions others

may offer. I listen open-mindedly to all

stakeholders without becoming beholden

to just one point of view. I believe

problems must be clearly defined, but

I think there is rarely only one solution

to a problem. Nor do I believe the NRC

always has the right answer to address a

given problem.

In my experience, often times the

best decision, the consensus-based

solution is reached through meaningful

dialogue among all affected stakeholders.

Let me give you an example. When

the Commission was assessing the

best approach to dealing with beyond

design basis external events in response

to the accident at Fukushima Dai-ichi,

the industry developed a concept for

Diverse and Flexible Coping Strategies

(FLEX) equipment and thus was born the

National Response Centers. To me, that

is a collaborative problem-solving effort

and innovation as its best.

What I hope is clear from my voting

record, my Congressional testimony and

20

NuclearPlantJournal.com Nuclear Plant Journal, March-April 2016